I am moved to comment further, despite my earlier resolution not to.

Firstly, some people completely misunderstand aspects of my approach to investing because they have a mistaken idea of what investing is really about. A classic is the following:

You are picking stocks. That is objectively imprudent because one can invest in index funds for very low cost.

@Marc defines my practice of buying shares in companies and holding them for years as "speculation" while his practice of choosing index funds is "investing".

@Marc is probably the only person in the world who thinks that.

Real investors study an investment opportunity and assess its merits before making a long-term commitment to it. They need to assess the dynamics of the business, how much profit it's likely to earn, the dividend and how it's likely to change, the risks to the business, etc. That simply can't be done with an index fund.

Another area of misunderstanding is viewing investments dichotomously as "equites" or "bonds". I see them completely differently. I buy some shares for dividends, some for long-term growth. They may both be called "equities", but they're completely different.

For "dividend" shares, I look at the current dividend as a percentage of the current price and try to assess whether it's likely to increase or fall in future. For "growth" shares, I look at the ratio of price to earnings and consider how both earnings and the P/E ratio might move in future.

For a quick example of the thinking summarised above, one of my "dividend" shares pays a yearly dividend of over 10% of the current share price. I'm satisfied that the dividend is safe for years to come. The dividend has never fallen - and has increased most years - since I bought my first shares in the company over 9 years ago. That's far more than I could get from an ultra-safe bond, so there's no way I would buy a bond when shares paying that high a dividend (safely, I think) are available.

One of the "growth" shares is on a P/E multiple of over 40. I bought shares in the same company in 2015 at a P/E multiple of under 20. I don't think its prospects are much better now than they were in 2015, so I'm thinking of selling some or all of my shares in that company. I only did this analysis now, when drafting this post. It's very - VERY - superficial, but it seems to support the impression that came through a few times during the current exchange, that the current hype about AI etc. has many similarities to the dot-com bubble that ended with a bang in 2000.

My conclusion may be completely misplaced- I emphasise that it was arrived at quickly and will need further checking. Also, I haven't been looking at the market recently because of my AE activities; however, it shows how I make decisions on my investments based on the simple metrics of dividend and earnings yield. It's not possible to do that with index funds.

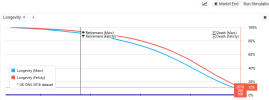

Another area of continuing misunderstanding is the hypothetical example of someone retiring from an ARF on 1 January 2000. I agree that someone who started withdrawing 4% a year from that date - based on the then market value (an important qualifier) - would have suffered a sorry fate. But it's not that straightforward.

@Dr Strangelove kindly posted figures showing how the index moved after 2000 and how the fund would have been depleted. However, I would like to draw attention to how the market moved BEFORE 1 Jan 2000. It is quite obvious from those figures that the market went mad in the few years up to 2000. That's not hindsight. It was clear as a pikestaff at the time. Here are the numbers (UK FTSE, but I'm sure the US was much the same - all figures are 1 January): 1996: 196.73 1997: 229.58 1998: 283.63 1999: 322.73 2000: 400.84. In other words, the market more than doubled in those four years - and in 1996 it was already 50% above its level three years previously. That should have led advisers to caution clients against taking (say) 4% of the fund's value at 1 January 2000, because of the risk that some of the windfall gains in the preceding few years might be reversed in future.

Finally, the only things of real importance for the investor are what it costs them to get into the market, how much they get back in dividends each year, and how much they get out at the end. Market movements in the interim are irrelevant. As Benjamin Graham said, the stock market is a voting machine, not a weighing machine. Looking at the example of the company mentioned earlier (current dividend yield 10%), the dividend yield was somewhat less than 10% when I bought it 9 years ago (I think it might have been around 8% - I don't have the precise figures to hand). The dividend has either stayed constant or increased every year since then. It doesn't matter a whit that the share price moved in a 60% range - up and down - in the last four years alone.

@Marc can do his wonderful lognormal and fat tail calculations, with a bit of Mandelbrot thrown in for good measure, on those price movements , but they mean nothing - if we focus on the weighing machine, not the voting machine.