Colm,

Why say things that are not true?

Firstly,

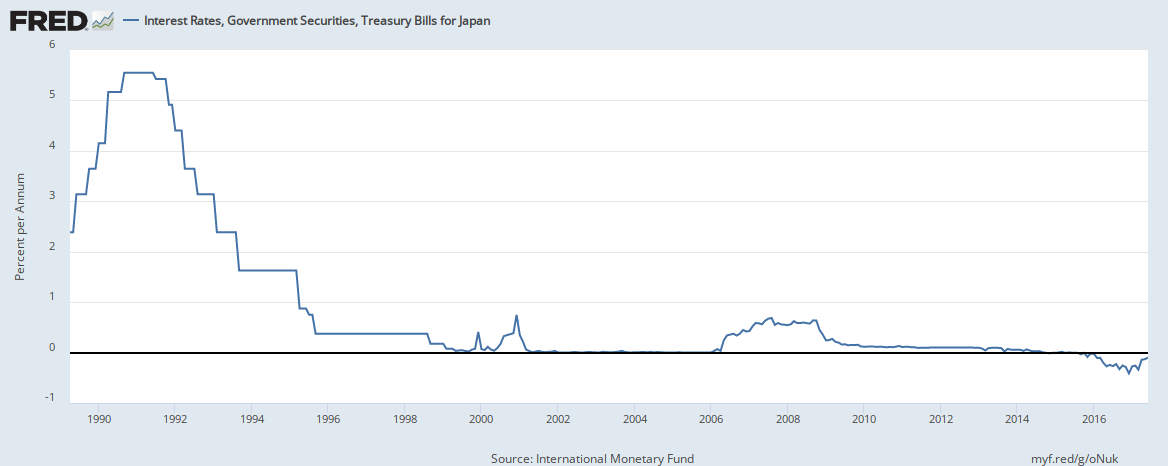

I don't have the figures to hand, but your 50% ignores dividends. With dividends, the conclusion is different. Also, I was using "cash" as a short-hand for money on deposit in Japan, earning negative interest.

Since January 1990 to date, the Nikkei has returned -19.06%...….that is with dividends reinvested. Thus, the central conclusion remains valid.

Note: Even before getting the figures, I knew that this would be the case. You can't have it both ways by claiming earlier that Japanese prices were in the stratosphere relative to earnings and that a portion of these same miserable earnings would subsequently be distributed as dividends and would somehow save the day.

Secondly,

As it happens, though, you have defended the strategy I'm unhappy with, of excessive belief in so-called "defensive" assets:

I don't have an excessive belief in defensive assets. I actually said the opposite in relation to holding excessive levels of defensive assets - as in: "excessively high or low allocation to return seeking assets should be a minority sport."

It follows that you made an accusation that was completely without foundation and that rather than acknowledge this, regrettably, you have tried Boris-like to deflect the issue by stating that I had said something that I hadn't said and by questioning my anonymous status! That bates Banagher so it does....

Finally, I am pleased that you have acknowledged that that people have different capacities to take risk. It follows that they need to determine an appropriate asset allocation based on their capacity to take investment risk. In designing this strategy, especially in respect of the income drawdown phase, sequence of risk is a real consideration...……...