@Marc

Fair dues, and thanks for sharing with us. I’m glad I'm not the only one prepared to share my innermost secrets.

For what it's worth, here's my approach to estimating how much of an "income" I can draw from my portfolio, and how much I think could be drawn from the sample portfolio Marc shared with us.

I learned my trade in the old world, before the era of stochastic simulations. Being stone age therefore, I look at financial questions firstly in deterministic terms, and then try to allow - more intuitively than scientifically - for the possibility (certainty!) that things won't work out as planned.

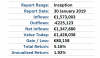

I have a spreadsheet, which projects expected investment return and pension outgo each month, starting from the current smoothed value of the fund (using smoothed values rather than market values is another story, too complicated to go into here; basically, I don’t think the market is always right). I also include a modest provision for contingencies.

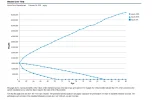

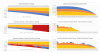

The aim is that, if expected returns are achieved, there will be enough in the fund to last us until we're well into our 90’s. If either or both of us kick the bucket sooner, there'll be something left in the kitty. I haven't factored our house into the equation. That’s a form of "insurance policy", in case the fund fails to deliver the required return or we live even longer than expected. The default assumption is that our home will form part of our estate.

My fund is invested exclusively in equities, with a tiny amount in cash. I expect an average return of slightly over 6% a year before charges by external providers, 5.75% after charges. (I manage my own investments to keep charges to a minimum). Plugging the 5.75% assumed return into the spreadsheet, the affordable pension is more than is needed for “survival”. However, I plan to withdraw an average of the affordable amount from the fund each month anyway. If times get tough, we can cut back, but I don't plan on cutting back otherwise: I much prefer to spend the money now than leave it for someone else to spend when we’re dead.

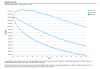

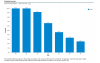

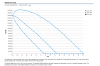

Looking at the portfolio Marc put up, I calculate an expected blended return of around 4.4% a year before charges. The calculation assumes a zero return on cash, around 1% a year on government bonds, etc. I won't go into detail on the assumptions for each asset category; that would distract from the core issues, but the message is clear: I expect a low return from low risk assets and a high return from high risk assets. I haven't allowed at this stage for the greater volatility of the high-risk assets. The difference between the 4.4% for Marc's sample portfolio and my 6% plus (both before charges) is the higher average risk profile of my portfolio, particularly that I don't have any cash or low-risk bonds.

From my (limited) experience of the retail financial services market, I estimate an average charge of 2% per annum on a portfolio of the type Marc outlined. That includes asset management fees, additional charges by the unit trust/ unit-linked fund provider, and finally the financial adviser’s fee/ commission. The 2% pa estimate for charges could be wrong - how far out I don't know. Thus, the expected net return on what I'll call Marc's portfolio is 2.4%.

If I plug a projected 2.4% return into my spreadsheet and assume the same level of regular outgo, I run out of money eight-and-a-half years sooner than I've assumed for my portfolio. Alternatively, the affordable "income" is much lower. The risk that things will not work out as planned is not as great for Marc’s portfolio as for my pure equity portfolio, but it's still a risk, which will have to be allowed for.

I suppose the main message I want to convey is that volatility of future returns is an important consideration, but the expected return, before volatility but after charges, is far more important in determining what level of “income” can be taken from a pension fund.