This is one of the most complex financial planning decisions given that you don't know when you are younger how your life is actually going to play out.

I saved in a pension in my 20s and I now have a significant pension fund. I'm 50 next year and can access it if I need to, which given that I have a 5 year old and a 9 year old is a distinct possibility.

Having saved in my 20s when I didn't have kids was the best financial decision I made. Because Its harder to do now even with more salary I have less disposable income.

I also bought a house, sold it and bought another one. The money I made on those two houses (with a preferential bank staff mortgage) was about half the amount I have made on the pension.

So, its not at all clear-cut what one should do. But it is clear that compound interest over a very long-time will ALWAYS tend to beat massive savings when older.

I think its important to consider where the money is coming from and also what are the alternatives you could invest in.

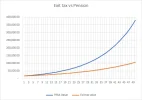

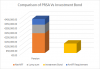

Let's say I'm 18 and Granny gives me my maximum CAT C exempt gift of €16,250. Let's assume I achieve average equity returns and I invest it to age 68. Let's compare that to an investment which pays exit tax at 41%. Keep everything else constant. No changes in tax rates and ignore the additional benefit of the income tax relief that I could offset against my salary when I start work.

Based on current rules, you would be looking at the following set of options in retirement (or an annuity) or some other set of rules that don't exist yet so I wouldn't get too hung up on the actual splits.

So that's just comparing the benefits of genuine tax free growth over 50 years.

Given that there is what, €3 billion in Prize Bonds currently, I think there is a fairly strong case to be made for Granny to give junior a couple of grand to supercharge his/her future....